FORT SMITH, Ark. — A crisis is defined as a time of intense difficulty, trouble, or danger.

Frequently, local law enforcement encounters someone who is experiencing some sort of crisis. In recent years, more has been learned about mental health and what a mental health crisis looks like. However, there are still misconceptions that therapists, like Meagan Beerman with Emerging Hope Therapy, are working through.

“There’s so many stigmas and labels put on mental health, that I think that a lot of times that’s what keeps people from even reaching out and seeking help,” Beerman said.

Locally, these stigmas have had a significant impact when looking at the number of adults who have a mental health illness and the care they can access.

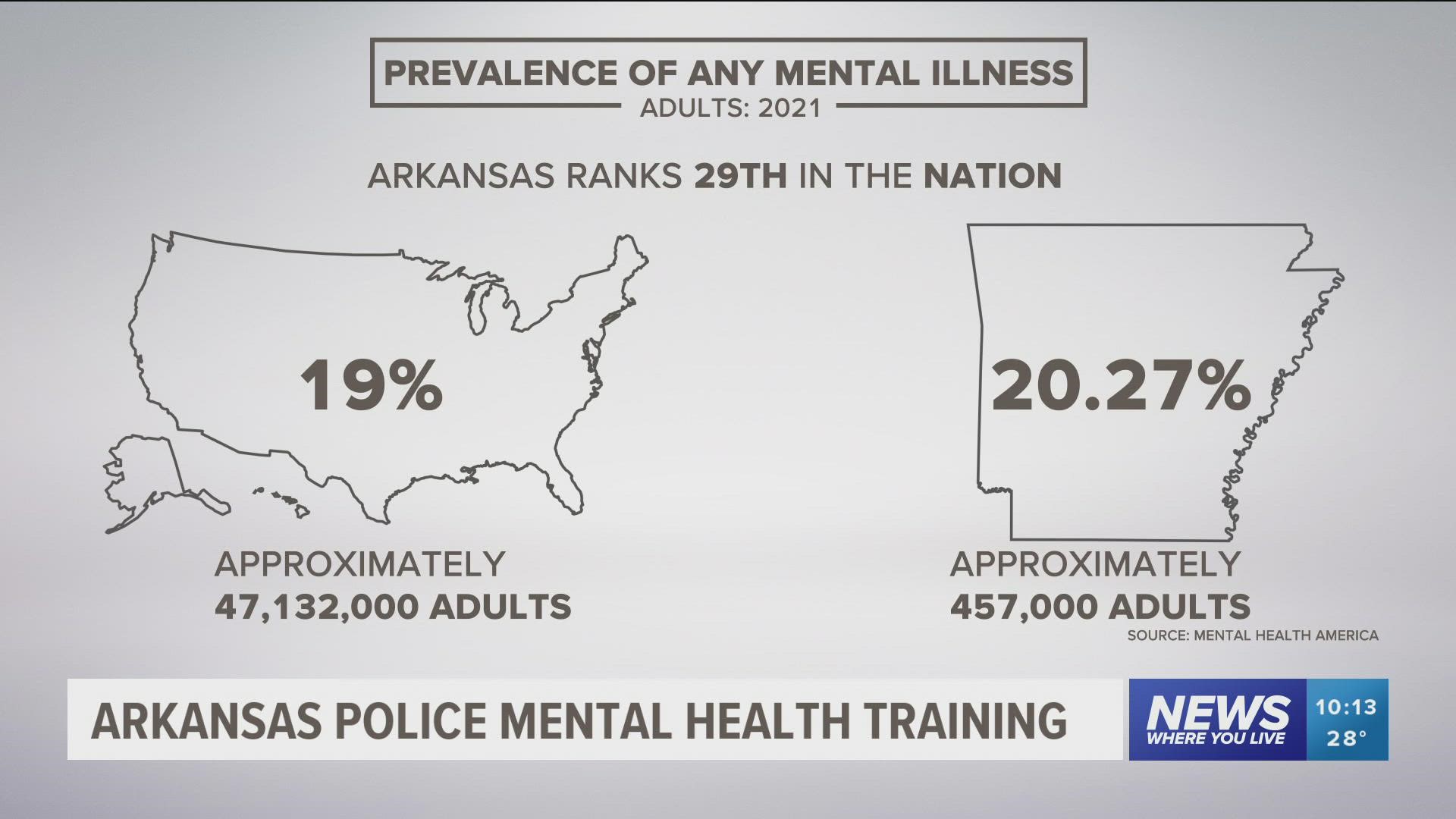

To put it into context, Arkansas has approximately 457,000 adults reporting any form of mental illness or about 20% of the adult population. This figure is slightly higher than the 19% of adults in the United States with any form of mental illness.

While on the surface, it appears Arkansas is in line with the rest of the country, where the state has a stark difference when looking at year-over-year trends of adult Arkansans with mental illness and their access to care.

Since 2017, Arkansas has ranked in the bottom half of the country in both categories.

It was in 2017, that Arkansas lawmakers signed Act 423 into law, in an effort to reverse these trends.

Joey Potts, the Director of the Five West Crisis Stabilization Unit says one of the main goals of Act 423 was to “decrease the amount of mental health clients who end up in jail, not because they’re criminals necessarily, but because their behavior has created a situation where there’s nowhere else to take them.”

In accordance with Act 423, the Arkansas Law Enforcement Training Academy, or ALETA, has worked hard to increase training and accessibility to train law enforcement from across the state to be in compliance with the law.

ALETA has implemented Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Training following the “Memphis Model” and encourages at least 20% of any law enforcement staff to have completed a minimum of 40 hours of CIT training.

“This class involves mental health professionals and some law enforcement instruction to help guide the officers through the process of encountering and working with someone who is experiencing a mental health crisis,” explained Charles Ellis, a retired ALETA trainer.

The course is designed for officers to learn about what a mental health crisis could look like in its various forms and ways to help assess and engage with someone who is experiencing such a crisis. Officers are encouraged to ask questions and hear from mental health professionals, watch videos of real-life situations that went right or wrong and determine what the officers did in the situation for the result that happened, and work collaboratively to come up with scenarios and work as a team to solve them.

Tactics many officers take away from CIT training include, how to de-escalate, body language, proxemics, effective communication, and patience. Ultimately, the goal is to keep the individual and officers safe in any given situation. CIT training is a key tool for Arkansas law enforcement to utilize day-to-day.

The Fort Smith Police Department became the first department in the state to implement a crisis intervention unit as a result of Act 423. This team of officers has undergone the necessary ALETA CIT training and is specialized in handling mental health crisis situations.

“A large portion of our department are trained in crisis intervention recognition and training and how to de-escalate such situations,” said Fort Smith Police Lieutenant, Steven Creek. “Our crisis intervention unit are experts at this,” Creek continued.

Beyond the classroom training, Lieutenant Creek and his team have recently begun to train officers in real-life situations through the safety of virtual reality. The new technology and system fully immerse officers into simulated programs designed to test critical thinking skills towards de-escalation without risking the safety of the officer or the individual.

Fort Smith Police Captain, Wes Milam says he is thankful to “have a board of directors that recognize the need to properly address the mental health crisis in the city and is able to give us funding to buy equipment for us to better address these needs and to better train our officers for these needs.”

The city of Fort Smith has become an epicenter to the positive results of Act 423. Along with having the first crisis intervention team and becoming the second department in the state to utilize virtual reality training, Fort Smith is home to the first crisis stabilization unit (CSU) in the state.

The Five West Crisis Stabilization Unit opened its doors on March 1, 2018, and helps serve citizens from Sebastian, Crawford, Franklin, Logan, Polk, and Scott counties. The unit has also become the model for the other three CSUs that have opened in the state in Washington, Pulaski, and Craighead counties. Their locations can be found here.

The four CSUs in Arkansas have become vital resources for those experiencing a mental health crisis. Kathryn Griffin, the Justice Reinvestment Coordinator for the Governor’s Office told 5NEWS in an email that since Five West Crisis Stabilization Unit opened, over 7,200 people have either been served or admitted at one of the four CSU locations across the state. Additionally, over 2,400 individuals have been diverted by law enforcement from jails or emergency departments, putting one of the key components of Act 423 into practice.

Experiencing a mental health crisis is not a crime. When law enforcement encounters an individual in the middle of a crisis the best thing to do is safely de-escalate the situation and determine the best course of care. The four CSUs in Arkansas are another tool officers can use to offer as a solution to a problem. These centers are completely voluntary and open to the public, not just individuals who are in the middle of a mental health crisis and have come into contact with law enforcement.

Potts says, “when you give someone a choice, they are already making a commitment to their own recovery, so, we always celebrate that when they get here, you’ve already made a great choice.”